Andrew David Russoli

An Unfinished Life: Andrew David Russoli

Memoir by Michael Usey

November 2, 2005

When my sons were young, they called him “Androot,” as in, “Are we going to Androot’s house for  Thanksgiving?” We were often guests at the Russoli’s home, as many of you have been, and my boys loved to be in the presence of Andrew. He was all boy, and had a great collection of toys guns and knives, which he generously let my boys use, as well as a collection of disturbing action figures and skulled-headed monsters. These were treasures to any boy under 12—in fact my sons inherited some of these action figures when Andrew moved from being a boy to being a young man. I remember one thanksgiving that Andrew had been to the dollar store to buy some cool plastic guns the color of sherbet for my sons, and they spent the time after dinner reconnoitering the Russoli backyard, coming in after dark covered with dry leaves and big smiles. Andrew could be kind and thoughtful, and young boys like my sons looked up to him. They do still.

Thanksgiving?” We were often guests at the Russoli’s home, as many of you have been, and my boys loved to be in the presence of Andrew. He was all boy, and had a great collection of toys guns and knives, which he generously let my boys use, as well as a collection of disturbing action figures and skulled-headed monsters. These were treasures to any boy under 12—in fact my sons inherited some of these action figures when Andrew moved from being a boy to being a young man. I remember one thanksgiving that Andrew had been to the dollar store to buy some cool plastic guns the color of sherbet for my sons, and they spent the time after dinner reconnoitering the Russoli backyard, coming in after dark covered with dry leaves and big smiles. Andrew could be kind and thoughtful, and young boys like my sons looked up to him. They do still.

Most of you know how Andrew died. He was in Nasser Wa Salaam, in Iraq , with the other Marines in his Cat Black team. Andrew’s responsibility was to protect Iraqi civilians and police from attacks and intimidation from insurgents. The Marines received a tip that there was a bomb in an open field. Andrew jumped into an armored Humvee with two other Marines. As they approached the bomb, insurgents watching from a distance detonated the massive bomb. The bomb was really made for an Abrams tank so the blast was extraordinary. His friend, Lance Corporal Adam Packet, was watching from a rooftop with two Marine snipers. When three insurgents jumped out of a car and started running, the Marine snipers immediately killed two of them and the third confessed after questioning. Andrew’s death was instantaneous. The events of his death are significant because they give us insight into how he lived. On the day he died, Andrew was defending civilians from a bomb blast, and his body bore the brunt of that defense. He died to help others live, the very essence of Christ’s teachings on living for others, and dying to self.

The Hebrew Bible reading is a scene from David’s terrible grief over the death of his son, Absalom. Through it we hear a heartbroken father’s cry, which gives us a small window in the abyss of grief Roland and Sally are feeling. It matters not about Absalom’s intentions being right or wrong. David’s cry is the wail of every parent who has lost a son or daughter in war. There is a hole in our hearts that will not be filled. When I told my friend Chuck Rush about Andrew’s death, and our devastating grief, he wrote back, “When I watched my son walking from me at the airport on his way to Afghanistan, I was thinking that he still walks the same way he did in footy pajamas.”

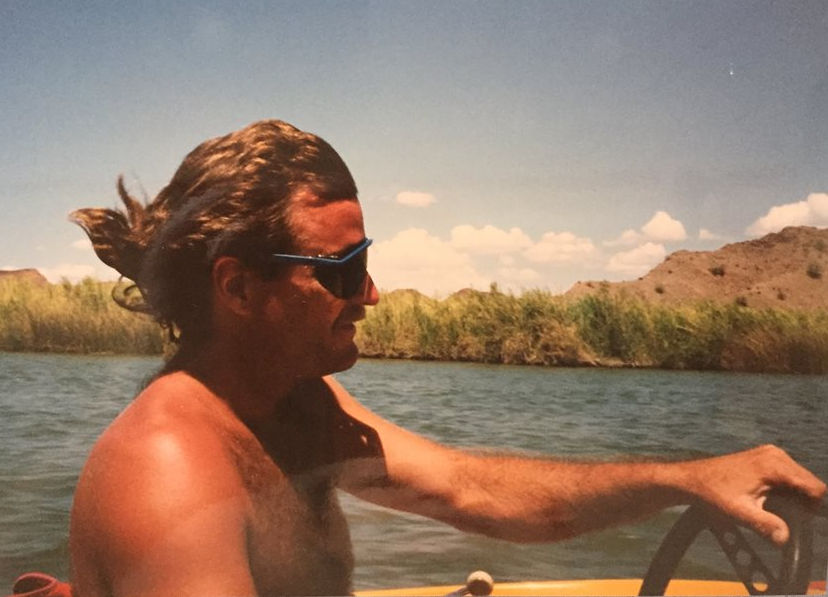

It would not be too extreme to say that Andrew was a warrior born. Being a soldier was the first and last thing we wanted to be. Born in Hollywood, Florida, in 1984, Andrew was an extremely happy child, as you might surmise from the pictures on the front of the bulletin. While he was being potty trained, he used to set up vast armies on the bathroom floor, bend over waiting for one invasion or another. His parents could send him to bed, and he went on his own without a fuss. He would tell his parents: “Sweet dreams, Dad, Mom; I love you.”

His family moved to Greensboro when he was 5 years old, and here in this town Andrew fascination continued with all things rough and tumble. He was a fighter of some sort for every Halloween: Ghostbuster, Pirate, Ninja, Navy Seal, James Bond, Batman, Marine sniper, complete with gilly suit. Do you detect a pattern? His 7 th birthday party was typical of his boyhood: it was a pirate party, complete with tattoos (the fake kind, he would get a real Marine one later), breadstick fights, refrigerator box pirate ships, a final hunt for Blackbeard’s treasure. When the treasure chest was finally found, and the goody bags within past around, one of Andrew’s young friends asked, “How did Blackbeard know our names?” Oh, the wonder of youth.

Andrew and his friends used to dress up in camouflage and head outside to play Creek Patrol, in which they moved stealth fully over the landscape and returned with good stories, pink cheeks, and camouflage clothes covered in mud. He wrote his own MacGiver Handbook, to help himself out of trouble. He never wanted to play the bad guy, telling his mom, he always wanted to be the “honorable” one. Roland remembers taking Andrew fishing one day when his son was 13. That day they caught nothing. However, an hour into the fishing trip, Andrew noticed a golf ball on the bottom of creek they were fishing in. He waded in and retrieved it, then he saw another. By the end of the day, he had harvested over 200 golf balls, in the creek which, as it turns out was near a golf course. Later he sold them at a yard sale (the perfect mix of his mother and father). Andrew was never afraid to get down and dirty.

I remember another time Andrew got wet. I baptized that boy here at College Park , in that font, in those waters. I can’t tell you how much it hurts to be burying this all-too-young child of God, and how my own grief must pale to that of his parents. We always have a baptismal statement in this congregation, and, in his, Andrew compared his life to an empty lasagna pan that needed to be cleaned. An excellent analogy, as real and earthy as an eleven-year-old boy’s imagination. His love for life nourished us, even then. In the Christian tradition, we speak of a person’s baptism being completed at death, since they are joined with Christ in both life and death. Nevertheless, Andrew’s is an unfinished life.

Junior, his brother, remembers a time when their grandmother, Ma, began throwing up blood when the boys were alone with here. And it was Andrew, then only 13 years old, that knew what to do and kept his head about him. He covered her with blanket, called 911, and stayed calm. Even though there were 15 years between Jr. and Andrew, there was no sibling jealousy between them, only affection and lots and lots of coarse jokes.

Andrew was a natural athlete, and excelled at most all the sports he attempted. Yet he never played any of them for too long. He played T-ball, gymnastics, basketball, and soccer until he was in middle school. He loved fencing, which he took for years, and when he ran out of boys his age to beat, he fenced with adults. He studied Judo and played Lacrosse, that most excellent sport in which you get to beat each other with sticks.

Andrew loved poetry. He wrote poems, including several concerning Roland’s days as a medic in Vietnam . He played the piano beautifully, although he didn’t stick with it. He played in the Jazz Band in Middle school. He loved to read. Once on his first tour of duty, he emailed the church that he was bored to tears, lamenting he was out of books. I answered that call, mailing him over a 100 books in the next month or two ($50 buys a load of books at Ed McKay’s), until he emailed me that his book stack was his night stand. Since he was on the top bunk, he had enough books now, thank you very much, and that I had provided enough reading matter for the entire platoon. He told me most of the soldiers didn’t care for the war books, having lived out those stories, and much, much worse. But he liked thrillers, science fiction, historical novels. He ended his email with this plea, “Please, for the love of all that is holy, no more books.”

He loved movies, especially ones with lots of action, like The Transporter, Sniper and Black Hawk Down. He loved the movie GI Jane, and was always trying to get the women in his life to see it. He relished the quote from Demi Moore, “Failure in not an option.” There is something so College Park in his love for a movie about a female making it into the Navy Seals. He identified with Romeo and Juliet, which provides a clue into his psyche: Romeo92 was his first IM name.

He gained from movies a clarification of his philosophy of life. One of his favorite movies wasFight Club. He told Sally one day, “My life is based on Fight Club.” She has no clue what he meant. (I could say more about Fight Club, but the first rule is, you don’t talk about Fight Club.) At one point in the movie, Tyler Durden, played by Brad Pitt, says this about the men around him:

I see … the strongest and smartest men who’ve ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see squandering. … an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables; slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy [stuff] we don’t need. We’re the middle children of history. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War’s a spiritual war… our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day we’d all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very [angry].

Tyler Durden’s diagnosis of the slavery of materialism and the vapid nature of male life is right on target, and in line with a Christian understanding about the idolatry of materialism. Tyler ’s answer was anarchy; Andrew’s answer was strength and honor.

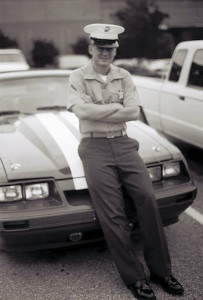

The phrase “strength and honor” comes from the movie Gladiator, another of Andrew’s favorite movies. It was an encouragement Roman centurions use to give to their troops before battle. Andrew and his band of brothers said it to each other before missions and firefights. He signed his letters and emails with these three words, and it is not too much to say they were his creed. So it’s fitting that atop his tombstone it will read Strength and Honor, the code he strove to live by.

Roland called his son “an adventurer, a fine Marine, and a sweet, sweet son.” He was all these things. In a very real sense, Andrew was living the life he wanted to live. He boldly sought out his military adventure. He chose the Marines, arguably the toughest branch and some of the most well-trained. He volunteered for Marine recon, the forward units who probe out contact with the enemy. He volunteered to be on the 50 caliber machine gun, the person the enemy targets first. He volunteered to learn how to clear houses of enemy combatants, which meant going first into buildings, into the teeth of harm’s way. And, on the day he was killed, he volunteered to drive the Humvee out to find a bomb that would either kill his fellow soldiers or civilians. Marines have always been the sharp end of the stick, but Andrew wanted to be on the very tip, the sharpened point. He lived the life he wanted to live, and in that, he lived with courage and honor, and the more dangerous, the better. Too many of us drift through life, never choosing to live with valor. Not Andrew; he chose his life and lived it to the hilt.

When he was in Boot Camp at Paris Island, I was on a mission trip with our youth to Miami. Jeff Sasser and I sent him suggestive postcards, from his group of troublemakers to one of their own who was missing. My postcard featured a line of buff guys in the Miami surf in teeny-tiny swimsuits. On the back, I lay it on thick: “All the guys say hi. Remember don’t ask, don’t tell.” Later on he told me that his sergeant had read both postcards aloud, without reading who they were addressed to, and Andrew thought, whoever this guy is, he is so completely unlucky. Then when his name was read, the platoon laughed for several minutes, and he had to do a thousand push-ups.

Andrew was not into things, although he had a good knife collection, mostly from his father, and a red Mustang only he could start. In fact, when he bought the ‘Stang, it had four-on-the-floor, a high speed shift, the racing package. Roland said, I didn’t know you knew how to drive a stick. Andrew said, “I don’t, but how hard could it be?” One time during his first tour he was driving a truck when a bomb exploded nearby. The entire truck was cover over in sand and dirt, and every witness thought Andrew was dead. Taking a page out of his favorite action movies, Andrew simply gunned the gas, and the truck burst out of the sand dramatically, he said, “Just like the movie The Man in the Iron Mask!”

Andrew was extremely tough of body and spirit. As you saw that beginning of the service, he was awarded the Purple Heart, for injuries during his first tour. It is likely that he was deaf in his right ear, due to being too close to too many explosions. He did not care to get tested, as this might have caused an end to his military career. Once during his basic training, he was out to dinner with Sara and Roland. His cough was so bad he was coughing up blood. He said, “It’s nothing to worry about.” Sara saw him at her office, and noticed he had a major rash from his feet to his chest. How’d you get that? Sleeping in wet clothes for 48 hours, I guess. Another time he told her he was concerned because he couldn’t feel his feet. What have you been doing? Maneuvers. How heavy was your pack? Oh, 150 lbs. No wonder he couldn’t feel his feet. But I never heard Andrew complain about any of these injuries. On the Monday before his death, he was talking to Sarah Rogers on IM, telling her he’d lost part of his ear that day from shrapnel. He treated it like it was a paper cut.

He could be wild and amazingly funny, but he was also very quiet and shy as well. Roland took him on a trip to Allentown to see his relatives when Andrew was in high school. Roland was looking forward to talking with son on the 8-hour trip. Well, the first 4 hours up Andrew slept. And when he awoke, typical teenaged conversation: How’s school? Good. Tell me about your friends. They’re fine. Andrew would have hated all the attention he is getting today, and he eschewed celebrity status. One of the great tragedies about Andrew’s early death is that he was just beginning to forge an adult relationship with both Roland and Sally. He loved both his parents fiercely, and they adored him.

Andrew grew up in the youth group at College Park. (In fact, he took part in several youth groups at all the churches Sally was connected to, and Young Life too. Maybe it took 4 separate youth groups to keep him on the straight and narrow.) One of my favorite memories of him was at Unidiversity, a summer youth camp with several other churches. As we were about to leave, Andrew saw a cute girl he wanted to say happy trails to. So he leapt from our moving bus with his flipflops on. He spun out and landed on the curb, wrist first. It was broken. (But in typical Andrew fashion, it took him two days to notice the pain.) On that same trip before his junior year, I told him I wanted him to be a role model and a leader to other youth. He answered that he’d think about it; and the next night he told me, no, he didn’t want to be a role model or a leader. Which he became anyway, without his consent, because he was a natural leader. Look at pictures from any youth event from his seven years here and you will see Andrew. He has an Eeyore type personality about Youth Group. He acted unexcited and nonplussed about most every event, but he always came. In fact, Dorisanne came up with the Andrew policy for youth trips: Andrew wouldn’t sign up to go to camp or on a mission trip, and deny he was going, until the day before, and he always went. So she began saving a place for him knowing this was the way it was going to go down. Like the first son in Jesus’ parables, Andrew said he wouldn’t go but then ending up going. On a deeper level, he wasn’t that articulate about his faith, but he did live it out. It was his feet, rather than his lips, that did the talking.

Andrew had his dark side, like his father and brother, and all of us. He could be rude: he didn’t suffer fools gladly, and I have seen him ignore people, even beautiful women, who wanted his attention. He smoked, which I suppose made his feats of physical prowess all the more impressive. Roland had sent him a box of cigars recently—which, according to Big Steve, is a requited addition for Jarheads. He could be hard to motivate, as all those who tried to convince him to do something he didn’t want to do discovered, be it teachers, youth minister, or parent. And some part of him was into the bravado of being a soldier. Perhaps that is part of every effective warrior. When I asked him once why he wanted to be a soldier, he said he wanted to blow [stuff] up, or words to that effect. But while that bravado was partially true, it was a long way from who Andrew truly was.

After he gave the focus one Sunday in church, which is included in the bulletin, he received a standing ovation, which is quite a rare thing from a reserved congregation like ours. He had asked me to be able to give that talk; however, he enjoyed acting like I had forced it upon him. He really was shy, despite his courage. So I took him to lunch at the Village Tavern the following week. He told me that he had seen great acts of courage and unspeakable horrors. He told me wonderful stories of Marines connecting with Iraqi children, and giving away some of their own food to these kids, collecting supplies for Iraqi schools, toys for injured kids. He also told me he had nightmares, that some of his favorite movies he could not longer see. He had been a part of a military action that had resulted, not only in the deaths of many of the enemy, but also of some civilians who were either caught in the field of fire, or who were shielding the enemy. Their faces haunted him. This is a reminder to us all that our servicemen and women carry on our behalf psychological as well as physical wounds. But this conversation reveals a part of Andrew that I liked so much: he was able to be both a fine Marine and to be critical of the myths of war. Andrew toyed with idea of going to college in Florida after his time was up, and he was really taken with the idea of being a firefighter. He told me, “From now on, I want to save lives.” Andrew was a Marine, no small thing in this “me” oriented world of ours. Andrew was bright, and his experience was leading him to a thoughtful understanding of his role and purposes. Like all of us, Andrew was a work in progress.

And where is God in our grief? Last Sunday I said that I trusted this brave congregation to ask whatever it will of God. As I’ve said many times, devout defiance pleases God, and by that I mean, asking and demanding of God, being willing to cry, shout, and rail at God, all in the context of our relationship with God, and as a part of our worship. I hope all of you understand that you can bring all of yourself to God, and that God craves that kind of relationship with us, one without hiding or pretension, as if we could actually fake out God.

Still I wanted to say what I trust is obvious: God is not responsible for our beloved Andrew’s death. God did not cause Saddam Hussain to torture, to starve, to maim, and to kill his own people. Nor did God start America ’s war with Iraq . God was not the one who sent Andrew off to war; Andrew chose that road, out of a deep part of himself, which as you know was equal parts courage, honor, and bravado. And God certainly did not cause evil cowardly men to explode a bomb that killed him and two other Marines 12 days ago. Human beings did this, not God. Human freedom, to act and to choose, is given to us by God, and it’s a wonderful and terrible thing. Every human being may choose good or evil, and the rest of us must live with the consequences. Fortunately for us, God’s specialty is bringing good out of our evil acts. If we let God, God will work with us to morph the evil (both done to us and by us) into good. In that sense, God is our divine alchemist.

In my understanding, this life is boot camp, meant to toughen us and to prepare us for the life to come. For the next life with God is, in my opinion, one of service. This is life is about forging a soul out of our commitments and loves; this life is about learning to give your life away. In short, this life is about learning to die to self and life for others. You can live until your 80 and not learn that, and I’ve buried a few that never did learn it. And you can be 21 and know that the secret of life is service for God and your fellow human beings. You show your love for God in the way in which you treat other humans. Andrew knew how to serve; he was a serviceman in the moral and noble sense of that word. He did not live a long life, it was unfinished, yet it was filled with bravery and valor. All of wanted to see the man he might have turned into. But the man he was already had become was kind and courageous, brave and loyal, filled with God’s strength and honor. He was, after all, Marine recon, those who go before us to scout and to show the way, to clear a path. He has gone before us, and even now works in God’s service. He will be there when we die, to give bear-hugs those he loved and left too soon. Here was a boy with training and courage who served, and even gave his life. His life shows us the way, the way of valor. Until then, Andrew leaves us with his creed to live by: Strength and Honor.