Maston Payne Stone

Memoir by Michael S. Usey

September 19, 2009

Psalm 19 is one of the Bible’s most elegant poems. The psalmist moves from the majesty of the universe to the splendor of God’s law. At first glance, it looks like the writer shifted gears between verses 6 and 7. After six verses devoted to the sun, moon, and stars, all of a sudden the law of God bursts onto the scene. It looks like a big shift, but there is actually a tight linkage.

The connection has to do with both the beauty and the orderliness of the heavens. Everything we see throughout the physical creation is the glorious work of an ingenious Creator. The stars that twinkle, the sun that shines, the clouds that scud through brilliantly blue noonday skies all bear witness to the grandeur of the God who fashioned each and every one of those remarkable things. To those with ears to hear, whole oratorios of praise to God are being sung constantly. The universe is one giant opera house that features a never-ending production of lyric melodies, achingly beautiful arias, and soaring crescendos of joy to the Creator.

To the psalmist, the splendor of stars like our sun point to a God who is clever, exceedingly wise, and finally good. God has been generous in sharing this universe of wonders with the rest of us. God wants us to enjoy the variety of splendor. We are blessed just to have the ability to see it all. John Calvin once said that the reason God created us to walk on two feet instead of going around on all fours like an animal is precisely so that we can stand tall, lift up our heads, and see the stars above.

God didn’t want us to miss the glories of creation. So God gave us eyes to see creation’s glories and ears to hear its chorus of praise. God gave us tastebuds and a sense of smell to enable us to enjoy wine and food. God gave us minds capable of taking note of all that we experience in the world. Humans made in God’s image are, so far as we know, the only beings on earth who are able to reach beyond themselves to enjoy otherness. We take delight in paying attention to creatures unlike ourselves.

White-tail deer in the Blue Ridge Mountains don’t keep a running list of the different birds they encounter. But we keep such lists all the time. We fill whole libraries with books that catalogue every conceivable kind of prairie grass, bird, tropical fish, flower, tree, and star. We love taking note of beings that are not like us. We’re born curious, as the parent of any three-year-old can tell you. “What’s that? Why is the sky blue and grass green? What do worms do down there in the dirt? Hey, Daddy, let’s stop to watch this ant hill for an hour or so!” Maston was the kind of father and grandfather that loved for children to notice and love nature.

The heavens declare the glory of God in a universal language that needs no translation from German into Dutch, from Farsi into Japanese. It’s a universal tongue whose grammar and vocabulary are intelligible to anyone willing to listen. When you view the universe this way, then you start to trust any God capable of making such wonders. What’s more, you take joy in any God who so obviously wants the rest of us to enjoy the universe the same way God does. God cares for us. God’s invested in our lives.

Of course, there are always those who look through telescopes at distant wonders, who learn how outrageously vast the universe is, who look at our own Milky Way galaxy and its mind-boggling 100 billion stars (and the other billion galaxies) and they then conclude, “Obviously, we human beings are nothing. We’re a galactic footnote so tiny, so insignificant, even if there is a God out there somewhere, God’d have to strain to see our puny little planet, much less take note of any individual person on this cosmic speck we call the earth!”

The psalmist will have none of that. The wonder of God is that God is at once the Creator of splendors that dwarf us is also the tender God who loves each person and calls each by name. God does know we exist and so has given commands and wise ideas to help us make our lives as comfortable and productive and safe and happy as possible. Any God who can create the universe can be trusted to give us the straight scoop when it comes to ways that will help us get along better in the world God made.

So the psalmist is not changing the subject or shifting gears between verses 6 and 7. Instead he’s following a consistent line of thought: creation teaches us that we serve a great, good, and reliable God. This same God has given us a roadmap for life, and so we follow that map with the joyous assurance that God will not lead us down the wrong paths.

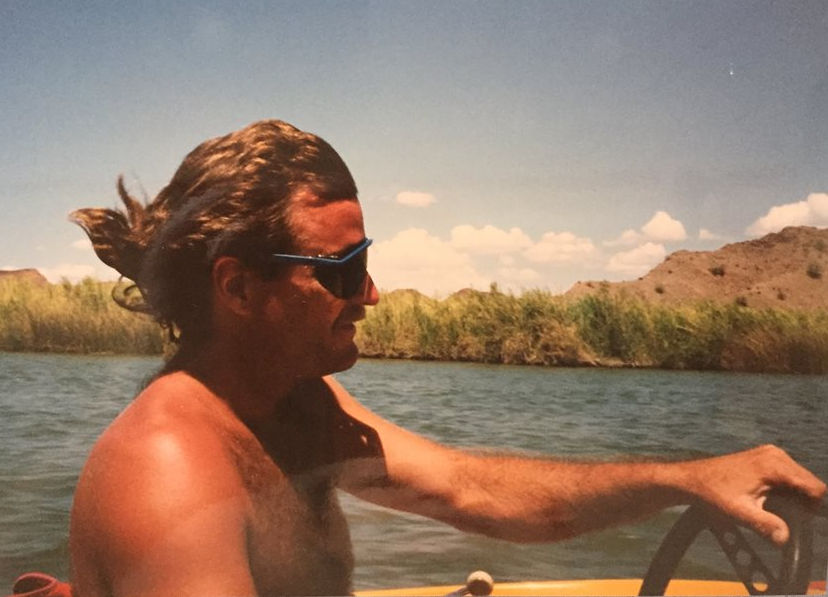

Mary Ann, Annette, Cynthia, and I chose this psalm on Thursday afternoon because we thought it was a perfect blend of what Maston Stone loved: the outdoors, his family, and God. Outside and in, Maston knew where to find God and delighted in both.

I first met Maston in the spring of 1994. Ann and I had flown to Durham from Atlanta to interview with the search committee. Maston was on my search committee, and my wife Ann remembers meeting him for the first time as a polite, kind man with laughing eyes and a good judge of character. But we saw his handiwork before we met Maston. The day before we interviewed with the committee, we drove from Durham to Greensboro to check out College Park’s building. The grounds were gorgeous: azaleas were popping out pink, red, and white, and Maston had nurtured flowers everywhere. Maston and his family kept the church grounds up for many, many years, and it always looked tip-top and hand-groomed.

After working he would periodically seek out moments to visit with me, sometimes sharing about things dear to his heart and sometimes just sharing and visiting in that easy, meandering way of his. He also made very intentional connection with me by inviting me—and Ann as well—to a very special yearly dinner sponsored by his keenly valued Civitan group honoring Civitan members’ ministers. I remember him, at each meal he graciously treated us to, rising from his chair, clearing his throat, and very thoughtfully and deliberately, with articulate decorum, introducing me and my wife. It was a loving gift he gave me every year I could go, and it made both of us feel very special—truly an act of love and grace on his and Mary Ann’s part.

Maston and Mary Ann joined CP in 1954. Margie Kent invited them here: they were living in a duplex on Aycock about 5 houses down the street from us now. Both were members of the Brethern church—both had been baptized in the Tacky Branch Creek, and neither would hear of being rebaptized in order to become a member at CP. They were accepted into membership, perhaps the first non-baptist baptisms to be accepted here.

Maston was a member here 55 years, and he has held most every position imaginable: deacon, RA leader, Sunday school teacher, Building and Grounds committee member, Missions and Personnel too, Search committee member (you can blame him for my being here), Ground Keeper, just to name a few.

Born in Thomasville in 1926, Maston was raised on a family farm with his grandfather, Jehu Randall Stone. I think the Stone family has the best names of any: his great-grandfather was Bloomfield Stone, and his parents were James Ruffin Stone and Fleeta Carmel Stone. Jehu, his grandfather, was a justice of the peace, surveryor, blacksmith, carpenter, farmer, and Sunday school superintendant. Couples would come to the house to get married, and Jehu would marry them, and many times Maston was a witness. Since some of those times he was under 14 years old, he liked to joke that those marriages he witnessed as boy were not legally married. His earliest memory is of sitting on his grandfather’s lap in church on the seat of distinction (reserved for the SS superintendant) in front of the prayer rail.

His other grandfather, Charlie Sanford Payne, was also a great influence in Maston’s life. They were close, and Maston raised tobacco on his farm his last two years in high school. Maston would drive his grandfather around in his Model A Ford, and Charlie would give his grandson his Virginia Cherol Cigars, which made Maston feel big. Charlie paid Maston $1.50 a day summer and fall of 1942 to work on his farm. So his two sets of grand-parents would forge in Maston the loves of his life: family, growing, and church.

His mother and father, James and Fleeta, were both the youngest of their families, both the seventh of seven kids. Maston was the first born of eight, seven of whom survived into adulthood. He had a brother, Charlie, who died of rheumatic fever at age 17. Maston was 19 years older than his younger sister, Judy. Maston had lots of distinct memories of his school years, memories that Annette asked him about and wrote down. This was a very wise thing to do, without which these memories would have been lost.

His favorite was his fourth grade teacher, Effie Payne Veech; she was instrumental in shaping Maston’s life and meant a lot to him throughout her life. For example, Maston borrowed money from her to buy his first car in 1945, a ’37 Willas that cost $300.

In his senior year of high school (43-44), he went to work for A&P in Thomasville, part-time for $.30 an hour. One day Maston was standing around talking to the produce manager, when his supervisor (Mr. Rackley) said, “Stone, we are not paying you 30 cents an hour to stand around and talk.” Maston also remembered that a fellow employee named Worthy once was rolling a box of price labels and spilled them on the floor. When a man bend to help him, the man asked him what he was doing. Worthy said, “Some son of a gun (or words to that effect) from Charlottte is coming and we have to get everything in order.” Of course unknown to Worthy was the fact that the man talking to him was the forementioned SOG supervisor from Charlotte. The workplace hasn’t changed that much, an incident right out of The Office.

When he moved out of produce into the meat department, Maston would find his life’s work as a store manager and butcher. He went to work in Dec 1944 full time, since he had graduated from high school in spring of ’44. Because of his work ethic, he was offered a promotion to Market Manager if he would move to Mooresville. He went home jubilant and found his mother washing clothes on the back porch with a Maytag ringer washer. His mother was not happy at the news: “Maston you can’t leave home; you’re only 17 !” But times were tough, and he had been offered $35 a week, a sum he said he’d have gone to Hong Kong for. He rented a room for $9 a week, and caught the bus home every Saturday night to go home, where his dad would meet him at the bus stop at 11 pm. Then he’d leave there on Sunday night to return to Mooresville. Once after the VP of A&P markets came by, the VP sent Maston a congratulations letter calling him the “Baby Market Manager.”

He moved around different stores in NC, including Eden, where he meet Mary Ann. She was working at a bakery, Tasty Pastry, which was 3 doors down from the A&P. Mary Ann would send Maston cookies by via a lady named Locky, and he in turn would send Mary Ann a dill pickle. Their first date was to a corn shucking at her parents’ home in Leaksville. He said, “The love bug bit us both.” This was in 1949, and they were married in 1951. Maston joined the Church of the Brethren—one of Mary Ann’s requirements. He and Mary Ann were married 58 years, and were each other’s best friend. They loved being together.

He would hunt squirrels in Vonnie Regan’s woods. One morning early Maston was hiding behind a tree when Vonnie came out to go to the bathroom. About the time Vonnie pulled his pants down, Maston shot a squirrel. Maston said later he’d never seen anyone pull up their pants faster and cuss at the same time. When Maston was younger, he lost two toes in a hunting accident. He had rested the barrel of his gun on his boot, thinking it was unloaded. When he grabbed it, it went off, and he lost this the first two toes on his left foot. Fortunately, this loss keep him from having a long career in the Army, the recruiters thinking his foot was not stable enough for long marches in snowy Korea.

His store career was cut short when, in 1980, he fell into his table saw at home, almost cutting off his hand. Cynthia was the first one to find him.

Despite this disability he was a terrific husband and father, and later grandfather. He loved David, Cythnia and Annette fiercely. Maston (and he alone) called Annette her pet name, Little Fat Girl. She and Maston always got up early together to enjoy the day. After they moved to the house on Westridge, he built Cynthia a cart for her pony, where he would take her on a ride over two creeks and down red road, which is what they used to call Hobbs. He took her in that cart on Halloween too, complete with a costume for the pony. Once when Annette was five, her first grade class was going to Burlington by train. She cried thinking her dad was leaving her, when she was only going for the half day. Maston taught Annette to drive a straight drive in his old Bonneville. She got caught on an uphill light on Hobbs, and sat there during several lights fighting with the clutch, until she made Maston get out of the passenger side and drive them home, while horns blared, while she slid over. She told him then that she was never going to drive a straight drive again. The next morning, Maston had her back in the car driving. His youngest grandson, Benjamin, called him “a man to look up to, a loyal man who did his duty to God country, and one who was my hero.”

He loved growing flowers and vegetables—I bet most of us here this afternoon have enjoyed some of Stone’s home-grown veggies. He passed on that love for Benjamin and John, Steven and Phillip. He wanted to teach his children and grandchildren to do things right. Maston hated clutter. He was, for example, very particular about where his tools were replaced when one of them used them. He wanted to be in the exact place he had for them so that he could reach them and find in the dark.

Like Psalm 19, Maston combined a great love for nature, family, and his church; in all of these he found God, whom he loved best of all. This is the reason it was so very easy to see in Maston our God, whose love last forever.

Looking back on Maston’s life, anyone who knew him will remember always with fondness his easy way with people—and I mean ALL people. He treated all people with respect and dignity, like what they said mattered, and that he was interested in them. My wife noted how he seemed to relish just sitting down and talking with a person—with no rush to get through an agenda of points. He showed interest in people by asking questions, he loved the comfortable back and forth of chatting, and, as he grew older, he loved to reminisce, honoring the memories and people of his past. So alongside his wonderful work ethic building a lifetime of good done for his family and the wider community, he managed to truly value people and enjoy their presence, social sharing woven into the fabric of a his work each day. That balance, his ability to enjoy the pattern of work, family, and all people put in his path, done with gratitude and love for God, is what each of us here today will sorely miss about him. And yet, by being the dear man of God he was, he has ensured that he will live on in our hearts, as well as in the very heart of God above.